This blog post will focus on essential cave books that everyone new to central Oregon caving should read or own. These books are primers for becoming familiar with central Oregon’s most popular caves. Anyone with a hint of curiosity about the area’s lava tubes will enjoy these books and find plenty of facts and history to absorb. The last section discusses harder to obtain guidebooks. They are usually handed out at regional caving events and paid for during registration. The camaraderie and good times had at these events are priceless.

Lava River Cave by Charlie Larson

Lava River Cave is a book dedicated to Oregon’s only commercial lava tube. It’s a slim book at 24 pages long, but Larson has undervalued his books so they are dirt cheap to pick up new at any retailer that carries them. Larson’s book on Lava River Cave is great for its history and old photos on the Sand Gardens, tunneling, and two maps. One map shows the entirety of the cave on pages 6 and 7. But the other map is segmented over the continuing pages and is described in great detail by Larson’s descriptive and methodical words.

This book is great for what it is, the only in depth literature on the cave, and a collection of history and photographs from decades past. Lava River Cave can be found for sale at the Deschutes National Forest office on Deschutes Market Road in Bend, the High Desert Museum and Lava Lands Visitor Center, both south of Bend on Hwy 97.

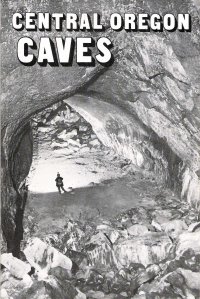

Central Oregon Caves by Charlie Larson

The other great book by Larson that is still available for purchase is Central Oregon Caves. Its main focus is on the public caves of the Deschutes National Forest with inclusions of a few BLM caves, a few caves from Willamette National Forest, and two privately held caves for completion’s sake. Like his other book “Lava River Cave,” Larson describes the caves in detail, but because of the greater selection included, each cave has a limited amount of space. This really isn’t a problem since you will want to explore and discover most of these caves for yourself. This book is chock full of goodies you shouldn’t pass up. Most of the caves have maps for them and those that don’t probably have a picture or two. Larson continues his geological review of the caves and you’ll find plenty to sink your teeth in.

Since the book’s creation, a lot has changed for the most notable caves of this book. Skeleton, Wind, Charlie-the-Cave, and Stookey Ranch Caves have all been gated in an effort to restore and manage the bat populations there. One thing that is not clear from the description of Stookey Ranch and Charcoal Cave no. 2 is that they are privately owned. Even though the gate design of Stookey Ranch is the same as others nearby, it’s still private property. If you find yourself staring at either caves without permission, you’re trespassing. Just an FYI!

Larson has had a huge hand in educating the public about these caves and having cultured more than a few cavers from his literature, including myself. His books are fantastic, cheap, and this book in particular should be your starting point. Central Oregon Caves can be found for sale at the Deschutes National Forest office on Deschutes Market Road in Bend, the High Desert Museum and Lava Lands Visitor Center, both south of Bend on Hwy 97. Pick this one up!

Geology of Selected Lava Tubes in the Bend Area, Oregon by Ronald Greeley

This little gem of a book is no longer for sale and hasn’t been for some time. It’s actually a geology book released by the State of Oregon’s Geology department in conjunction with the Space Sciences Division of NASA. This book can be read at the Central Oregon Community College’s library or accessed by inter-library loan through a public library. The book is meant as a study of domestic lava tubes for use toward lunar analogies, perhaps lunar bases in the future. But it reads fairly easily and has plenty of pictures and maps to entertain any cave enthusiast.

The book should not be used as a cave guide for exploration. Greeley has detailed a few caves from the Horse Lava Tube System that are on private property. There’s nothing like traipsing through people’s property to get in trouble with the law. So think of it as a vicarious look into those caves which are now out of reach. But fear not reader! This book has plenty of information on the Arnold Lava Tube System and other popular caves on public land like Lava River, Skeleton, Boyd, and South Ice Caves. Like Larson’s book, Greeley doesn’t note that some of the caves are on private property and this includes Charcoal Cave no. 2 and Stookey Ranch Cave.

Caves and Other Volcanic Landforms of Central Oregon by Lynne Sims and Ellen Benedict

This book was still available for purchase in some locations like the Deschutes National Forest offices only a few years ago but those copies may have been leftovers from the 1982 NSS Convention. Still, it’s easily acquirable through inter-library loan or perhaps even on Amazon, eBay, of Half.com from time to time. This book takes a different approach to exploring caves and the countryside. Most of the thrust of the book is on using car mileage to establish a route through the landscape to view volcanic features. Features reviewed in the book range from the Newberry lakes to Crack in the Ground to Derrick Cave. The book is illustrated with photos and artistic renditions of cave inhabitants like the elusive grylloblattid or harvestman to surface fauna like coniferous trees and chipmunks.

Harder to Obtain Literature (and some not so essential)

An Introduction to Caves of the Bend Area, Guidebook of the 1982 NSS Convention edited by Charlie Larson

This is the holy grail of local cave literature. The guidebook was specifically made for the 1982 NSS Convention that was held in Bend at the Mountain View High School. Most of the material was written by Charlie Larson, but credits also include Larry Chitwood for the geologic map and geology section, and Jim Nieland for the cartography though not all of the cave maps were done by him. Some contributions from Ronald Greeley and Craig Skinner are also included.

The 1982 guidebook is extremely difficult to come by now. It is sold out everywhere and has been for many years. A copy of it was available through the public library but it was never returned some time ago. The book doesn’t turn up on the auction sites or online booksellers. The best option currently is to know someone who has it and borrow it, or get a photocopied version.

Larson went all out on this book and packed in many caves found in his other book Central Oregon Caves and a whole bunch more, especially on less popular caves that you know are just nearby, but you’re not quite sure where. This book doesn’t help you find the caves since that’s not the intent, but it does give maps and descriptions for Button Springs, McKenzie Pits, Santiam Pit, the Matz Caves, Edison Ice Caves, Cleveland Ice, and many other caves that are sure to knock your socks off.

My personal favorite is the section on the Horse Lava Tube System which I have spent many a day studying and visiting with landowners. Aside from grotto newsletters, this book is one of the few sources of information on that system and the maps supplied sure do peel your eyelids back as you realize these caves are all near the city of Bend.

Guide to the Lava Tube Caves of Central Oregon by David Purcell

Okay, so I know I titled this blog post as “Essential cave literature…” but I couldn’t help but mention this little book. It predates all the other books by Larson and has much of the same format as his book but less finesse. You won’t learn much more from this book than you will from Larson’s books, however it does include a little bit of information on Malheur Cave and the lost Crystal Cave. Guide to the Lava Tube Caves of Central Oregon is no longer for sale either, and your best bet is to hunt it down online.

Pushing Passage at the Western Regional 2003 edited by Patti Williamson-Hughes

This guidebook was released in limited quantities to attendees of the 2003 Western Regional. Its intended destination was not for the public of course, but it’s worth mentioning to anyone who has more than a passing interest in local caves. The guidebook is slim and the production values are low, yet it packs a small punch with its collection of cave descriptions and maps. Most of the entries in this guidebook are not found in the previous books described above, and a few like Carburetor Cave are not found in any other book [Ed: Now found in Basaltic Bourne guidebook (see below)]. For that alone, it makes it worth a look.

Undiscovered Country, 2010 NCA Regional Guidebook edited by Matt Skeels

Edited by who? That would be me. Now I get to play the part of a self promoter. This book was created for the 2010 NCA Regional. Roughly 80 copies were made and they’re all gone now and in the hands of cavers. Much like the 1982 NSS Guidebook and the Pushing Passage 2003 Guidebook before it, I attempted to make it a collection of cave descriptions and cave maps. Many contributors helped in making this guidebook come to fruition including Charlie Larson, Brent McGregor, Jim Nieland, Ella Rowan, Larry King, Ric Carlson and plenty of others.

The most unique contribution to the guidebook are the maps and I created this book to be the “one stop shop.” Brimming with obligatory cave maps, revised maps, and new maps the most noteworthy of which is Arnold Ice Cave. Revised maps of Lavacicle and Skeleton Cave are also included, as well as rare inclusions of such caves as P Line Ice, Upper Breezeway, Cody Borehole, Parker, and many others. One of the shortcomings of the book is the low number of articles, but the 74 cave maps included outnumber the total number of pages in the book!

The Middle Ground, 2015 NCA Regional Guidebook edited by Matt Skeels, cover photo by Brent McGregor

Like its predecessor, Undiscovered Country, this book was published for attendees of the 2015 NCA Regional event held in Bend, Oregon and hosted by the Oregon High Desert Grotto. If I recall correctly, about 120 copies were printed up. It also checked off the box of having Neil Marchington on the cover. I had originally meant to get him on the cover of the Oregon Underground, but the right photo never materialized before I had stopped working on the newsletter.

The book took shape much like UC, in that the goal was to cram as much maps as possible and make it the one stop shop again. To that effect, this book has nearly everything UC does, plus a whole lot more. Nearly double the pages! One of my last communications with Larson before he passed that summer was making sure I still had a greenlight to use his material for this book which he graciously obliged. Other content providers include Steve Knutson, Brent McGregor, Larry King, Liz Wolff, Tom Kline, Jim Nieland, myself and others. There are a few minor errors in the book. I threw this thing together in the span of two weeks after completing a bat management guide for Oregon Department of State Lands, so it was a bit rushed. Notable error on page 48 is the swapping of “eastern” for the western lobe (paragraph 6).

Numerous smaller articles were added to this guidebook, including content on the LTB system, Potholes, Derrick, and the Sandy Glacier Cave Project. The main addition, and a featured trip at that regional event, was the Horse Lava Tube System. This 32 page article is my compromise for never having completed the book I wanted to do on the system. By the time this guidebook rolled around, my enthusiasm for tackling the HLTS book project had waned, so I threw in all of my completed maps, wrote up that article and called it a day. Many new maps are included, as well as rare reprints of Larson’s maps from the system, typically only available in the 1982 NSS Guidebook and Speleograph newsletters.

The Horse system article includes a huge backlog of never before published maps. They include Mushroom, Pop & Son, McKnight, dozens of spatter cone caves, Stairstep, Barking Dog, Dos Liebres, Covet Caves, Pronghorn Caves, and new maps of select Redmond caves. Other new maps: Lilly, Scat, Three Eyes, More or Less, Lake Billy Chinook, China Hat Road Pit, Lunch, Catbegone, Standing Arches, a new Malheur Cave map (one of Larson’s last contributions to this realm), a modified McKenzie Pits map, Duo Pits, as well as other rarely published maps.

Strangely, the one map not included in this book, is the joint WVG/OG surface and cave survey of Paulina Crack. One of the caves, Fissure De Jour, is depicted on the cover. Maybe in a future guidebook?

Post Edit: 9.5.2019

Basaltic Bourne, 2019 NCA & Western Region Guidebook edited by Matt Skeels, cover photo by Brent McGregor

In 2019 the Oregon High Desert Grotto and the Oregon Grotto co-hosted the 2019 NCA & Western Region event in Redmond, Oregon. This guidebook only had 53 copies made and featured 100 pages of smooth, glossy articles and maps. The laminated cover depicts Kara Mickaelson in Derrick Cave.

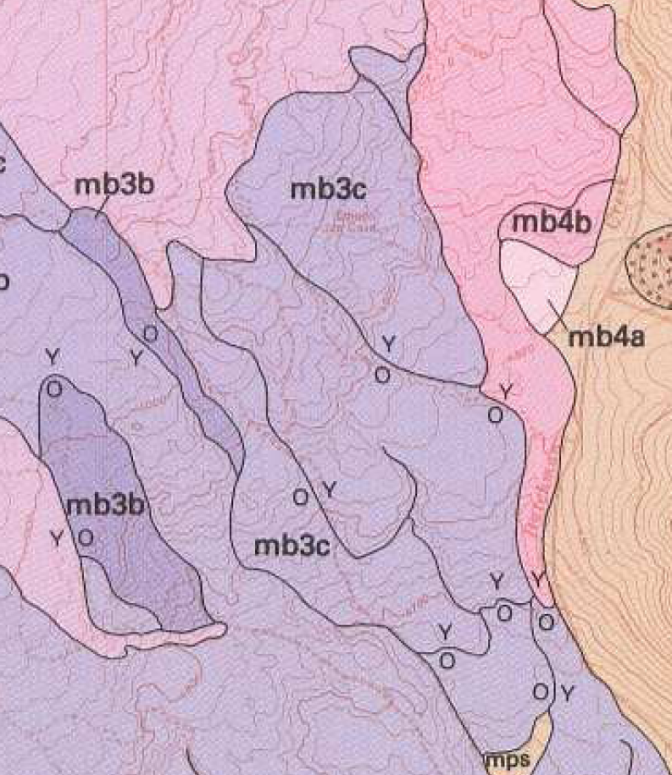

Articles include Causeway of the Volcanoes by Michael Partridge, Mount Bachelor Volcanic Chain (MBVC) by Matt Skeels, a lidar-derived geologic map of the Mount Bachelor Volcanic Chain (MBVC) by Matt Skeels, and The Derrick Lava Tube System by Matt Skeels. The Derrick article received a few corrections to its previous printing in The Middle Ground.

The guidebook features many of your staple maps of central Oregon, with special emphasis on the MBVC area. Plenty of new or rarely published maps also got published. Including maps of Pictograph, Hyphenated and Charcoal Cave by Larry King, Smorgasbord by Michael Partridge, Bone Tunnel Cone, Ventana, and Hitch Digger by Edd Keudell, Carburetor by Garry Petrie, Dutchman I and II, Sparks Lake, and Independence by Ric Carlson, Pronghorn Lodge Cave by Ron Delano, Paulina Crack by Tom Kline, and more. I also drafted a few new maps, mostly sketches. Some new surveys were also included as well as a hefty dose of modified versions of previous maps both of my work and others. A few maps of mine that were included: The Grove, Battle Axe Mountain, Crooked River Indian, High on the Saddle, Mad Skills, Last Call, Cricket Town, Jaws, Alpine Ranch and more.

While there are only three articles in this book, the centerpiece is the 30 page article on the MBVC that describes in detail most of the known caves in that area. With the advent of lidar, numerous caves have been discovered and added to our growing list of lava tubes. The most interesting guidebook piece is a lidar-based geologic map of the MBVC that revises the 1992 geologic map by William E. Scott and Cynthia A. Gardner of the USGS. The new map improves upon the 1992 map, identifies new areas of interest, as well as key areas of uncertainty. A presentation at the regional event explored some of the nuances of making a lidar-based map and identifying subtle lava features to constrain lava flows.

*******

Horse Lava Tube System Bibliography by Matt Skeels

I’m cheating a bit here, since this book has not been published yet, but a near final draft exists. It’s been cited as a source exactly twice: once in my work done for the Oregon Department of State Lands and the other in The Middle Ground. For now, it is strictly an electronic document. Always a work-in-progress, I constantly updated the document as I uncovered new morsels of information in my research. As of late, work has stopped and articles to review have all but dried up. A few internet articles could still be reviewed in the future.

This dry, but information rich document, is a 100+ page bibliography. In it, I’ve reviewed… doing some rough guesstimating in my head here… around 500 sources of information that mention the Horse system. I list the name of each source and give a detailed summary with review, correcting the authors if they’ve made a mistake, as well as supplementing my own information when the source is lacking.

In the future, I hope to reorganize the book, but that may be too large of an undertaking. I may just have to hope for a final review, fill in a few blanks, and publish a limited number of hard copies to gift out to friends and to those who contributed to my research. If that happens, I guarantee it is essential literature for central Oregon cavers, just not for beginners.